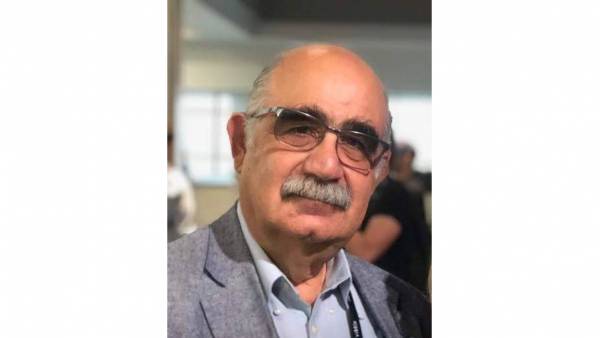

What's wrong with us?

There was once a world where TV stations tried to keep their audio levels within reasonable parameters while commercial producers did their best to make their messages sound louder. In fact, over the years the advertising production industry won that war and achieved the implementation of a series of mixing and audio processing practices especially dedicated to making their tracks sound BIGGER than those of their competitors. And now this tale is over...

What do we do to achieve a "BETTER" sound? Take advantage of the absurd accuracy of digital audio meters to compress audio signals in such a way that the content is always at the higher end of the available dynamic range, but eliminating peaks and transients so that in a PPM meter the audio signal appears within the parameters required by the broadcaster. NOMINALLY, of course. We generate intelligible mixtures but totally "glued to the ceiling". The effect of this practice is debatable in terms of quality, but the goal is achieved: The commercial is heard MORE.

The serious thing about the matter is that the problem has been leaving the scope of cuts for commercials and now invaded the programming space. TV channels want to sound louder than their competitors. And here I must be honest and insert a "mea culpa": For many years I have been working with organizations that overprocess audio, that compress the final mixes of their products and recompress them in the transmission phase. I myself have perpetrated many STRONG, FLASHY and POWERFUL mixtures ... and that depending on the experience of the viewer are simply OFFENSIVE.

Rules of the game

We've created a vicious cycle: If the sound intensity of the channel's programming is higher, advertisers aim to sound even louder to maintain the status quo. And we ended up YELLING at the viewers. And considering that audio meters continue to set valid levels, we are faced with a radical decision: We need to change the paradigm of sound measurement. We have been trying to measure volume for almost 120 years, but to have real control over how our products are heard we must start measuring loudness.

Real sound

Sonority – which in English is known as loudness – is a perceptual quality of sound. Attention: We are talking about sound, not audio. In nature, each sound source has particular conditions that determine its sound, and these conditions are always subject to the environment in which the real sounds are generated. Every sound engineer with some experience knows that each musical instrument has a different behavior when its sound is recorded, and the resulting audio signal is measured using VUs and PPMs. Physics makes a bass louder than a bandola, and it is inevitable that a cymbal "covers" the sound of a violin. A point to ponder: The conventional arrangement of the instruments of a symphony orchestra depends precisely on the characteristics of each instrument ... and was established centuries before amplification systems were invented.

Musicians speak of the "timbre" or "color" of each instrument, a rather subjective attribute that essentially describes the variations of each in terms of pitch, harmonic production, reverb, sound pressure, interference production, phase changes, falloff or attenuation with distance... and bandwidth. This term seems out of place talking about music but it is very important to define sonority.

Diverse sound

A spectrum analyzer allows us to visualize the strength of an audio signal by bands, that is, separating ranges of certain tones. This allows us to objectively measure the phenomena that make a bass drum louder than a violin. The bass drum generates a signal with high sound pressure at low frequencies. The violin, like all stringed instruments, tends to generate sounds in a very specific frequency range according to the tuning of each string and the skill of the performer. Metals simultaneously produce all kinds of echoes, interference, reverberations and turbulence. In fact, they are instruments with multidirectional diffusion patterns.

Considering these differences we can approach a useful definition of loudness. On the one hand, low frequencies move more air and reach farther than high frequencies. In general, an object capable of generating high frequencies cannot generate a very high sound pressure. And a sound source as anarchic as a trumpet generates sound pressure in many bands - that is, it occupies a large bandwidth in the sound space; in short, it sounds more, it is more sonorous. That's why many trumpeters use mute...

A murmuring crowd is louder than a screaming man. A camera set can be louder than a solitary and amplified electric guitar. The meow of a kitten can be clearly perceived "behind" the barking of an Alsatian. Conclusion: In nature, sonority is intimately linked to the real and diverse sound sources that surround us.

The perception of sonority is the result of a real and subjective experience. It is determined by the listening conditions and by the conditions of the human auditory apparatus. So the healthiest thing is to accept that the study of loudness corresponds more to the field of psychoacoustics than to that of electricity: These are human experiences, not voltage variations. Fortunately the science of perception can be replaced by a talented sound engineer who knows when to ignore your meters and work "by ear"...

Recorded sound

The sound is real and the audio is always a reconstruction of the original experience. That is why we must assume that the handling of the sonority of each of the elements of a sound mixture must begin in the register. Let's go back to the example of the mute: If a jazz ensemble that records in a studio of 60m2 does not attenuate the metals, there is not the slightest possibility that in the resulting recording the subtleties of the piano and the blows of the knee against the bass can be appreciated. That's why multichannel recording and all kinds of specialized microphones were invented. And this has more to do with knowledge than toys: Using a compressor to "reinforce" a voice cannot replace selecting the right microphone – or its correct location, among other things. A good producer is a sonority artist, not a volume manager.

And with this observation let's return to the world of TV: We must learn to measure and produce according to the sound, the real experience of the viewer. Things get complicated by the emergence of surround sound systems, because a poorly made stereophonic mixdown is marked precisely by loudness problems. Neurotic competition among commercial producers has begun to produce reactions in regulatory bodies that are responsible for ensuring the quality of the viewer's experience.

But the emergence of this regulatory interest is not necessarily positive. ItU BS 1770/1 has created a frame of reference that is only marginally compatible with the BBC's self-regulatory practices. The U.S. Senate is prosecuting the Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation Act, a bill that may eventually take on the force of law even against the opinion of the ATSC Committee and some consumer associations. Faced with this situation, DTH service providers that must respond to the technical standards of different markets have chosen to adopt automated sound adjustment systems that do a good job but are really not perfect.

Meanwhile, in Brazil there is important work in the line of self-regulation by broadcasters. And in Europe the EBU has chosen to work on the definition of its own standard that has significant differences with the work carried out by the ITU and ATSC. And the ISO is somewhat behind on the subject of measurements, unfortunately.

The regulatory landscape looks somewhat confusing. It is possible that in the coming months international standards will be established that in many countries will have the value of law as they are supported by international treaties. Now, we know that in our market the pressure to enforce these standards will not come so soon ... but it may be a good time to start studying the subject and evaluate the important offer of real-time loudness measurement and adjustment systems that the industry offers us. Let's not forget that the viewer irritated by the SCREAMING commercials is the one who has the power: he can always move his finger three centimeters to leave our signal and go to some other channel in which the commercials do not produce migraine.

| How to measure what you don't hear |

A VU-Meter, the old "needle" audio meter allows us to visualize the voltage variations of the audio signal. And since it works thanks to an electromagnet, it tends to attenuate the large voltage variations that require rapid movements of the mechanism. In fact, the very weight of the indicator needle makes it a meter of average values of the electrical intensity of the audio signal. To compensate for the shortcomings of the VU-Meters the BBC began to use since the late 30s some devices that it called Power Programme Meters or PPM meters. A PPM meter shows us the highest energy values of the audio signal. In short, a PPM meter measures extreme values of the audio signal - and only shows us what happens in an instant. The BBC's first PPM meters were basically extremely sensitive VU meters that reacted to a "spike" in the signal – essentially a voltage transient – and indicated its value by holding the position of the needle for a fraction of a second. Needle PPM meters have disappeared for decades: With the popularization of LEDs in the late seventies, PPMs of discrete or "bulb" units became the norm - and in fact they are the preferred meters for manufacturers of digital audio equipment, because a PPM meter is perfect for users who want to use the dynamic range to the fullest. Mico and eliminate the "peaks" to maintain the apparent legality of the signal ... just as we all do lately. Obviously, all kinds of hybrid meters have been manufactured to achieve a really useful measurement of audio signals: fast VU-Meters , slow PPMs, LED meters that try to behave like VUs, devices that simultaneously present peaks and average ... but none of these devices can overcome the limitations imposed by physics: Voltage measurements (or the sampling values of a digital signal) are essentially insufficient to adequately describe the loudness of an audio signal. There are too many factors that we have been ignoring in the last century... among others that audio is voltage carried by cables, mixers and other devices. Wouldn't it be better if we tried to measure sound?

|

Leave your comment