When an experimental group was shown two videos with different sound tracks (one recorded with less fidelity than the other, but with an identical image) and asked if there was any difference in the quality of the video, they answered that the version with the best audio was the one with the best image.

Most modern productions—whether audio-only or audiovisual—record sounds on multitrack devices, which record them separately in the same storage format (be it a tape or the hard drive of a computerized system).

To give an example, you can record on separate tracks the voiceover, the sound effects, the music of a piano and that of a flute. If the case arises and you would like to change the voice over later, you can re-record only that clue and leave the others intact.

The multitrack system allows you to process different signals independently. Suppose the voiceover sounds very "off"; it can then alter the frequency reaction to change the upper midrange frequencies and make them more intelligible.

Thus, the multitrack system provides flexibility but, at the same time, requires the "mixing" or process of conveniently combining and processing all these tracks to produce the best possible editing that guarantees quality and transportability (the ability to sound "good" in any audio system, from a transistor radio to a music lover's equipment).

The mixer or mixer

The mixer is equipment that "directs traffic" audio so that signals are combined (each with its own level control), routed to the appropriate destination, and produced a properly mixed output signal (usually in stereo). A mixer may seem intimidating, but it's actually made up of a series of identical modules.

If you understand how one of them works, you already know 90% of how a mixer works. Listing all mixer manufacturers can take up several pages, but some of the commonly used brands include Mackie, Soundcraft, Yamaha, TASCAM, Peavey, AMEK, RAMSA, and Allen & Heath.

To illustrate some basic principles of mixing, visualize a mixer of eight inputs and two outputs (8-input, 2-output). Following the example above, the four sound sources recorded on a multitrack recorder – voiceover, effects, piano and flute – would respectively feed four inputs of the mixer. These four signals go through, in turn, four controls (which determine the level) and then the combined signals feed a common stereo output bus (or connector bar) (which reaches the monitoring system and the main recorder).

Try to visualize the path of the signals as a vertical and descending fluid towards the mixer; and the exit path (or bus) as a horizontal fluid that from left to right "exits" the mixer (figure #1; we will discuss the problem of auxiliary buses later).

At the confluence of the input channels and the bus, you will find a level control. Since the output signal is usually in stereo, you will find there a control for each channel. If you turn this control over, you can place the signal anywhere in the stereo field (left, right, or center). The typical mixer has anywhere from eight to dozens of input signals.

Getting on the bus

The simplest mixers have only two buses. Most, however, have multiple buses (the standard is eight) that allow you to perform different types of mixes. Additional buses can be used for effects such as surround-sound or echo, or to create a monophonic version compatible with television.

Mixers are characterized by the number of inputs and outputs. A 24-in, 8-out mixer, for example, has 24 input channels and eight output buses. There may even be additional (or subgroup) buses that provide master volume control to individual channels.

For example, suppose you are mixing the different voices in a choir and assign each voice its own channel. Imagine, likewise, that the different voices of the choir are perfectly balanced. If you increase the overall level by manipulating each fadeer individually, you are likely to alter the balance. If these channels, on the other hand, feed a subgroup bus, the master control of the bus can change the level of the different voices simultaneously.

Each mixer has its own way of sending the signals to the buses. Options include a bus selection switch (in which a row of buttons sends the input signal to the selected bus) and send controls (similar to the main level controls, but powering an auxiliary bus instead of the stereo main bus).

Input modules.

Each mixing channel has its own input module to process or route the signal before sending it to the output bus. Typically, this module includes:

- a preamplifier for low-level signals;

- an indicator that warns if the signal exceeds the dynamic range of the mixer;

- a send control or controls (which route audio to auxiliary buses);

- very low frequency filters (cockpit murmurs or microphone);

- high frequency filters (wheezing and lisps);

- a stereo image placement control, and

- a general control of fading.

One of the most important components is the equalizer or EQ; imagine it as a sleek, flexible tone control. A basic EQ can enhance or decrease high-pitched or low-pitched sounds; a more sophisticated one can differentiate the controls for frequency, for power/decrease and for amplitude.

This will allow you to enter a specific frequency and manipulate either a narrow range (for example, remove an interference), or a wide range (to add "presence" or give "background" to the audio).

When mixing, it usually happens that different sounds occupy the same place in the sound spectrum; so to speak, sounds are "masked". An EQ can separate instruments by shifting the emphasis from one sector of the frequency spectrum to another. If the background environment, for example, interferes with the narration, reducing the reaction of the environment (in voiceover frequencies) can create a greater audio "space" for the narration.

Input modules frequently include connectors for inserting signal processors into individual channels. Of course, the topic of signal processing deserves a separate article, but let's say that its typical applications are compression (which allows to polish the variations of the dynamic range to achieve a more "smooth" sound), noise filters (which eliminate whistles) and reverb (which allows to create effects like simulations of a concert hall), among many others.

Another common feature in input modules is the preview button, which overrides all other modules and is useful because it allows small changes to be made to tracks that would normally be drowned out by the others.

The mute key serves the opposite function: it automatically cuts (or mutes) the respective channel and is wonderful for taking noisy signals out of editing until just before the time when we finally need them.

The output master controls provide an overall setting for the master stereo bus (many buses also have master controls). In other words, these controls change the level of any audio that is simultaneously feeding the bus.

Photoemitting diode (LED) multi-step meters typically use different colors to differentiate level ranges (green for "normal," yellow for "about to overload," and red for "overloaded").

The meters can monitor a variety of sources such as inputs, auxiliary buses and outputs of the master, among others. Some inputs have "activity" "LEDs" that light up if there is a signal, which can save you a lot of headaches when you've accidentally turned off the level control and you're not sure the signals are entering the mixer.

Digital control and automation

Many analog mixers use computerized digital controls to save commands or sets of commands (e.g., a particular combination of sound editing commands for the choir, soloists, announcer, etc.), as well as to dynamically record various editing "movements" such as successively raising and lowering a fade.

A digital control can be built into the mixer or can be obtained separately to install it. Digital control makes it easy to work with mixers. A computer can memorize all the control changes made and repeat them as many times as necessary.

For example, if the voiceover is required to be more prominent, only the mixture is repeated with changes in the level of the voice over and commands so that the computer archives only those changes, and leaves the other elements intact.

Computerized hard disk recording systems sometimes come bundled with "virtual" mixers. In these systems, all controls appear on a monitor under the model of traditional mixers, with a graphical representation of vanishers, knobs, meters, etc.

Beyond the mixer

There's more to mixing than mixer. Since a final mix of audio can be played almost anywhere or anywhere, most professionals listen to their edits on different speakers, to get an idea of what their edit will sound like in the real world.

It's about making a mix such that the resulting audio is acceptable on any system rather than making a mix that sounds great on one type of speaker, but plays poorly on another. In small studies, "close" monitoring is very popular; this technique uses small speakers (within walking distance) to minimize the influence of the acoustics of the place.

As with mixers, there are dozens of companies that manufacture monitors for close monitoring; Speakers from Event Electronics, Alesis, Genelec, KRK, Meyer Electronics, among many other brands, are popular in this type of studio.

Likewise, your audio edition is required to be recorded on a stereo master tape. The favorite tape on the market is currently the digital audio or DAT (Digital Audio Tape). Companies such as Sony, TASCAM, Panasonic, Otari, among others, manufacture tapes with this specification. The DAT digitally records two CD-quality audio tracks. However, the number of people using compact discs is increasing since they are more robust than tape and play on any CD device (more common than DAT machines).

We have hardly touched on the fundamentals of audio mixing, which is both an art and a science. Being able to produce a clear, unmistakable and well-balanced edition is a challenge. Fortunately, it is one of those challenges where experience makes the teacher.

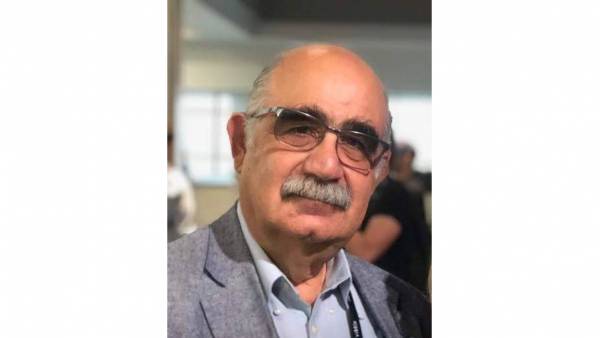

Note on the author:

* Music producer and editor: expert in musical electronics; author of Multieffects for Musicians and Home Recording for Musicians; technology editor of EQ magazine.

Leave your comment